The actor has gained a wealth of experience over the course of a career that stretches back more than 20 years in dozens of films that have achieved legendary status in Spanish cinema: Jamón Jamón (Bigas Luna), alongside Javier Bardem and Penélope Cruz; Historias del kronen (Montxo Armendáriz); La flor de mi secreto (Pedro Almodóvar); La buena estrella (Ricardo Franco); Son de mar (Bigas Luna); in works by directors such as Peter Greenaway (the creator of cult films such as The Draughtsman’s Contract), or in super-productions including Blow (Ted Demme), There be dragons (Roland Joffè), Colombiana (Olivier Megaton) and Riddik (David Twohy).

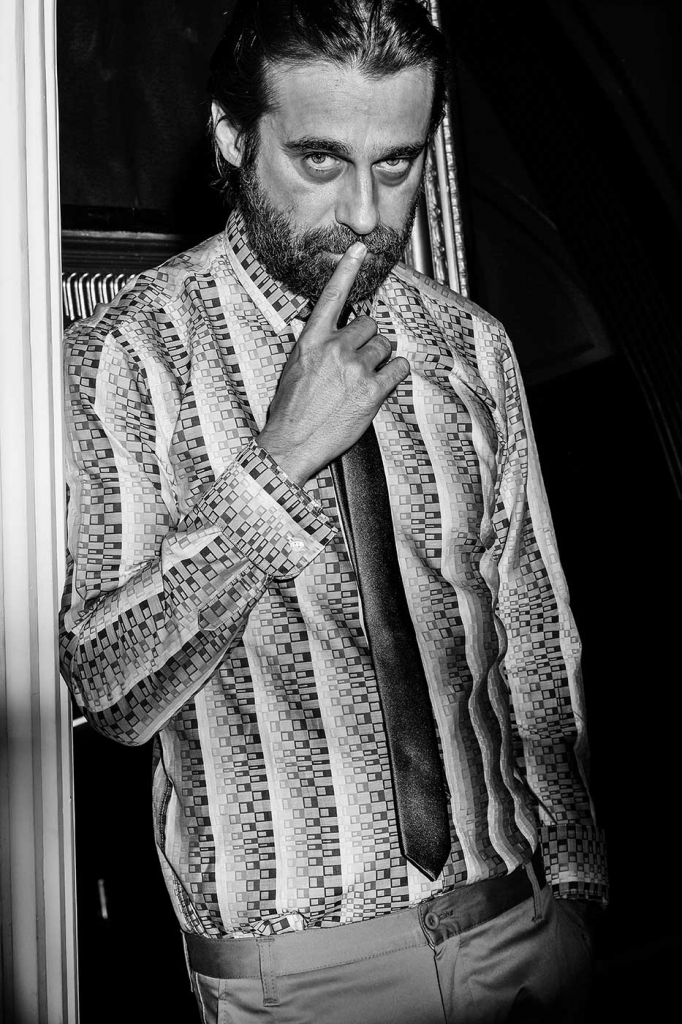

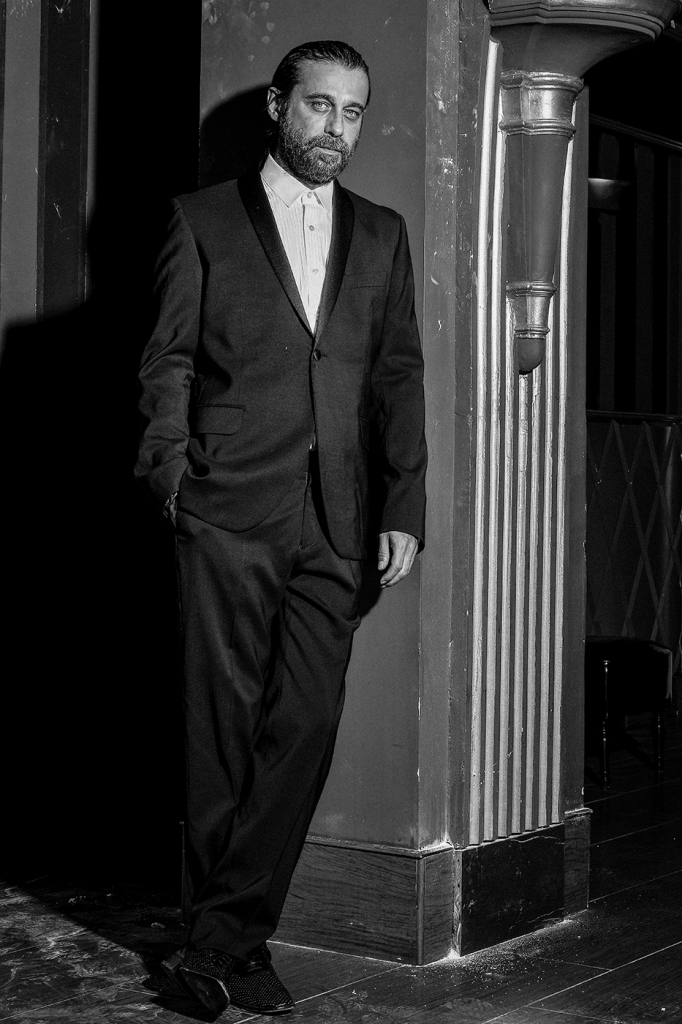

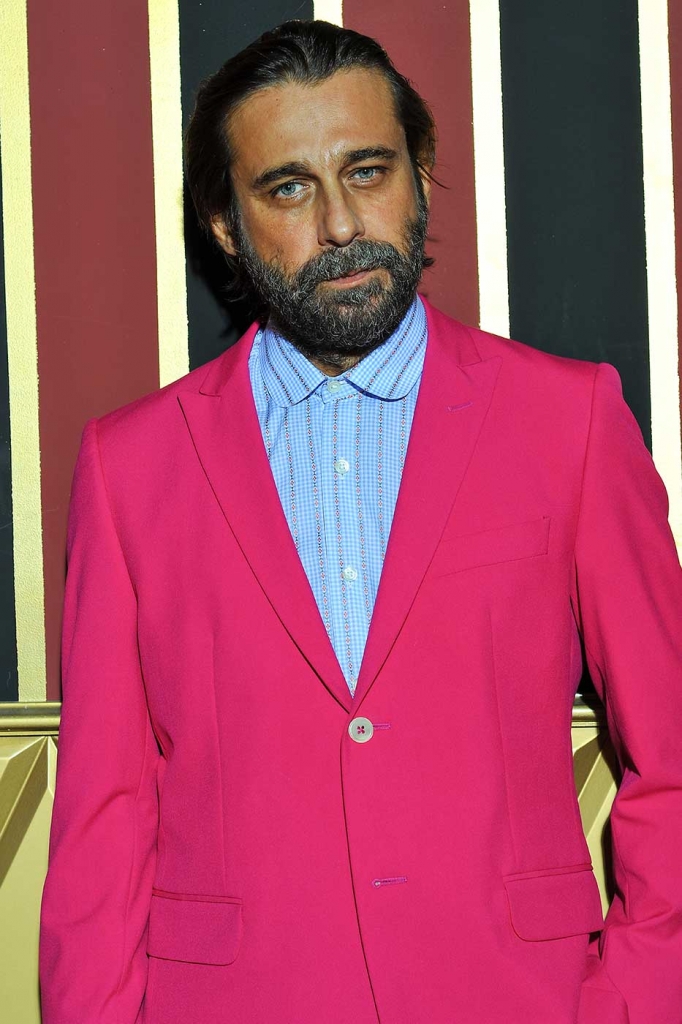

Jordi has worked a lot to become something more than a great supporting actor. What’s the next step he’s going to take? He has just returned from a stop-over in Milan, and before that he was in London, where he’s filming Criminal, along with Kevin Costner. He’s always got various irons in the fire at the same time.

What importance do you give to fashion and its world? There was a time when young girls and boys dreamt of being actors but now they all want to be models. Is fashion socially overrated?

When you take a peek at other fields, you see a new world. Just yesterday I was in Milan walking along Via Santa Tecla with a chief editor from Vogue and I was amazed by his sensibility not only when it came to fashion, but also architecture and the city’s paintings. For me, the word fashion has two meanings. One is haute couture which is reserved for a few people. The other, more common one known as pret-a-porter, I believe that it has done a great deal of good socially because it has given people an identity. It has helped many people from the middle class and middle to lower class to belong to a social group, to a tribe, and the result is that in the end, a young girl decks herself in rags and piercings and says to her mother: “Mum, this is who I am”.

In your opinion, what counts for elegance in a man? Do clothes make the man or does man make the clothes?

Elegance is a state of mind. In London I saw Cameroonians or Indians walking along the street wearing just a few pieces of material and trousers and I said to myself: how elegant! Above all, you have to be dressed, and not disguised. In Hollywood, my friend Johnny Depp, for example, is in a position to dress in a very special way and he has created clothes that have a grunge/bad boy touch that can look really good. On the red carpet you can see actors such as Joaquin Phoenix, Philip Seymour Hoffman (now deceased) or Antonio Banderas, dressing in a very normal way. But for the girls it’s more complicated.

As well as being an actor, you’ve been a painter for many years. Where does the need to paint come from? What inspires you: sensuality, melancholy? What are your personal demons?

Personal demons are good! They’re like outboard motors, driving you to do things. I have greater trust in the person who paints a monster than in the one who paints a sunset. For example, Francis Bacon painted corpses and people who were ill. But if you read interviews with him, you see that he was a great person and that he had a big heart. Who lies behind the exterior? I am an actor: one day I get out of bed as a pirate and the next dressed as something else: melancholy, sadness, all faces possible. The same thing happens with painting.

What do you miss about the golden Hollywood of the 40s, 50s and 60s, in the film industry, the actors or the films?

The truth is that I have not paid much attention to that golden era. I am more familiar with the Italian cinema of Passolini or Visconti, the French nouvelle vague or Spanish cinema from the 50s to the 70s. Nowadays, I believe that we are living in a huge paradox. We’ve lost much of our liberty: that generation of filmmakers went through the Second World War, but after that they experienced great freedom. Now, those above us want to sell us the idea that we are free, but it’s not true. We’re living in a kind of invisible dictatorship that we purchased. It’s not a state of war, but you see things that make you think, such as those people who were evicted from their homes by the police because they weren’t able to pay. The more apparent freedom we have, the less we transgress, and the less free we are.

In cinema, there was more freedom before: in El fantasma de la libertad, Buñuel had a group of bourgeois citizens dining while seated in toilet bowls. That kind of freedom doesn’t exist today when it comes to writing a script, except a few people who have reserved it as a kind of last refuge, people like Lars Von Triers.

From the current filmmaking scene, Spanish, European or American, who are the big guiding lights for you as a director, actor or actress?

It’s not easy. I’ll tell you an anecdote: a film agent once asked me to give him the names of directors with whom I would like to work. Of the 70 names that I gave him, it turned out that 40 of them had already died. But, in the end, of the 30 remaining, there’s no doubt that all of them are fantastic. It’s quite another matter to say with which of them it would work because, in practice, working is a completely different matter. With regard to actors, I like lots from Daniel Day-Lewis or Charlotte Gainsbourg to that old Spanish actor, Pepe Isbert. I’ve been watching his films again lately and I think he’s a genius.

Do you watch many films?

Yes, I watch films on video and I freeze the scenes over and over again. As far as I’m concerned it’s very intense, it’s more than you can digest, it’s like eating 20 suckling pigs. You learn that, whatever the result is, deep down, there aren’t any bad films, they all deserve respect.

Of all the performances you’ve given up until now, which one do you rate the highest? And why?

It’s very difficult to say because of what I was telling you before. In a way, choosing one means discrediting the rest. And that would be very unfair towards the profession: acting means commitment, an actor has to be there, they’ve signed up for six months or a year; it’s not like a make-up artist who can leave at any time if they want.

I have very warm memories of my films from the 90s, a time in which there was some great filmmaking in Spain, with directors such Bigas Luna, of whom I’m very fond, Alejandro Amenábar and Julio Médem. Also the film El cónsul de Sodoma, where I played the poet Jaime Gil de Biedma: I read the biography of the poet Miguel Dalmau, recited his poetry, and studied the DVDs and the audio archives with his original voice.

In Hollywood, while filming Blow, at the beginning I didn’t know what I was doing. Three people helped me enormously to find my way and they managed to get me to overcome my fears: Ted Demme, Penélope Cruz and Johnny Depp. Afterwards, I’ve found that connection with many others, for example, in Heart of the Sea with Ron Howard (the director of Cocoon, or A Beautiful Mind) who was an actor himself previously.

Alright, but I insist: which performance do you like least? Have you ever played a role that you are embarrassed about afterwards? Any mistake that you might have learned from?

Yes, on one occasion I let myself be influenced by the pressure around me. It was a painful situation in a film but I’m not going to tell you the name. At the time I didn’t want to play the role, but I felt obliged to. I learnt that an artist has to be fully aware of where they’re going, they mustn’t allow themselves to be dragged by a manager or a publicist. It was a lesson that came in useful for me when they offered me a role in Lost: I turned it down simply because I didn’t want to spend six months filming in Hawaii.

You’re filming your next film, Criminal, in London. What’s interesting about your role there beyond the fact that you’re surrounded by stars?

It’s a thriller by Ariel Vromen, with a spectacular cast that includes Kevin Costner, Gary Oldman, Tommy Lee Jones and Gal Gadot. When they offered it to me, I said to myself: with a cast like that here, they are going to kill me off by page five. But no: in the plot I play a computer hacker, an anti-establishment figure that can hack into any program, someone for whom the existing order of things has to be destroyed: the police, the law, the institutions, to build everything new again. Deep down, it’s very contemporary.

What kind of role would you like to do as the main actor? Would you prefer to play a famous person or a historical figure, or play someone anonymous, totally fictitious?

Playing a historical figure helps a lot. At times I’ve mentioned Dalí, Jesus Christ or Eugenio (a great Spanish humorist who is no longer with us). But an anonymous character is a pearl hidden in the sand. For example, take Passolini’s Accatone: the protagonist is no more than a poor person, and nevertheless he gives the impression of immense strength: his anger, his faith, and his contradictions: at the end he kills himself on a motorbike, saying: “at last”.

Looking ahead, do you see yourself getting deeper into directing or will you continue being basically an actor?

Actor! I see directing as something that is more occasional. Directors ought to be born with a lifespan of 250 years because it takes so long to carry out a project; there are a thousand things you have to struggle with. Directing is a thousand times harder than being an actor.