When Kodak founder George Eastman promised more than 120 years ago, “You press the button – we do the rest,” photography began to become accessible to everyone. A success story took its course.

Steve Jobs completed this story with the development of the smartphone: You press the button – there is no rest.

The photograph as a means of communication has become faster and even stronger than writing. Since the smartphone, we all live with a flood of images of indescribable proportions. It is said that the viewing time of an image is shorter than its exposure time.

The photo designer Norbert Tölle tries to escape the arbitrariness of the digital photo.

He finds it outside the visible light spectrum. At the lower end of our spectrum, visible light turns into heat. This is the infrared range. This light is invisible to our eyes and cell phones. But there are films that are sensitized to it. They have been used in military reconnaissance for aerial photography, among other things. Procurement is complicated, the material is in yards and usually overlaid for decades. It often has thermal damage, fungal attack, or other degeneration. These defects are visible later and are deliberately incorporated into the image. The film grain is like the noise and crackle of a vinyl record.

Norbert Tölle spools this Infrared film, 70mm wide, perforated on both sides, (the format is well known to cinema fans) in cartridges developed by Nasa for the moon landing. As a camera, therefore, only the same type comes into question, which also documented the moon visits about 50 years ago, – “The Queen of Cameras” – a Hasselblad 6×6.

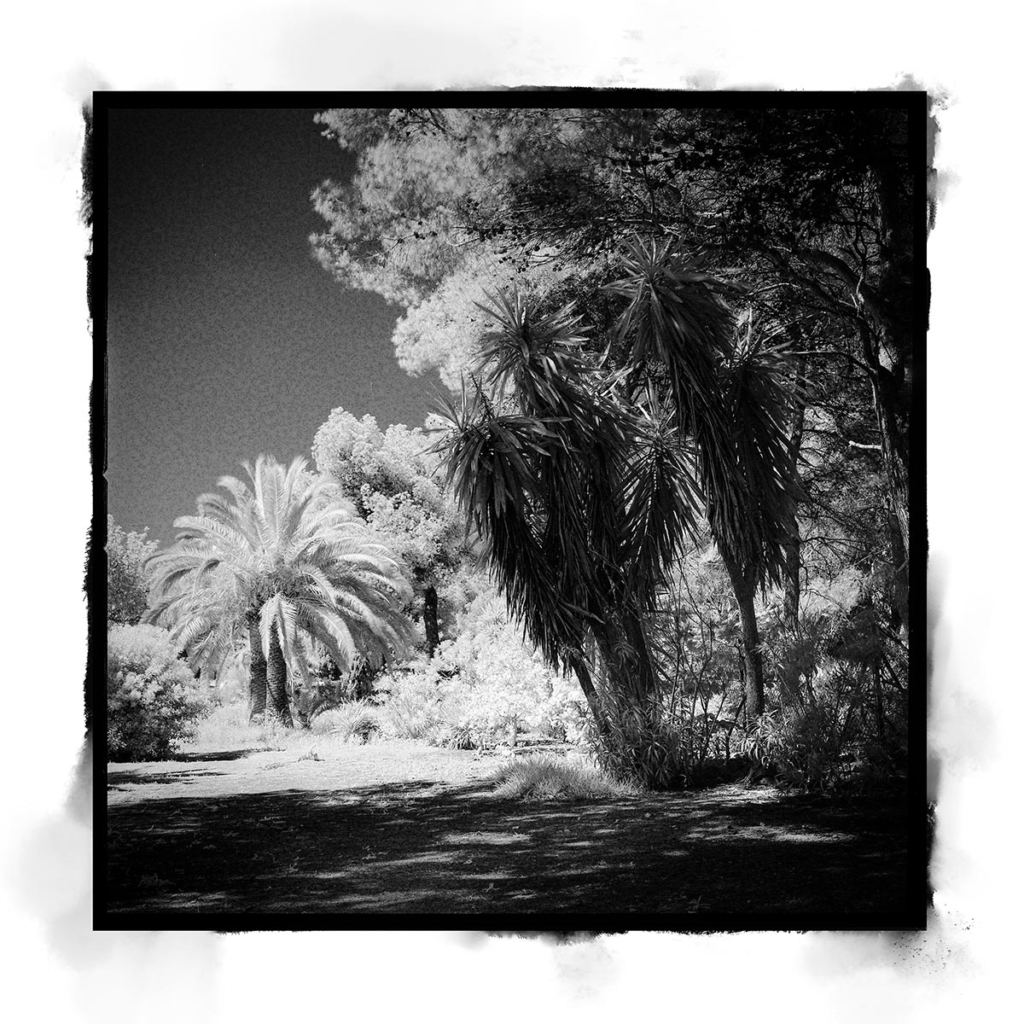

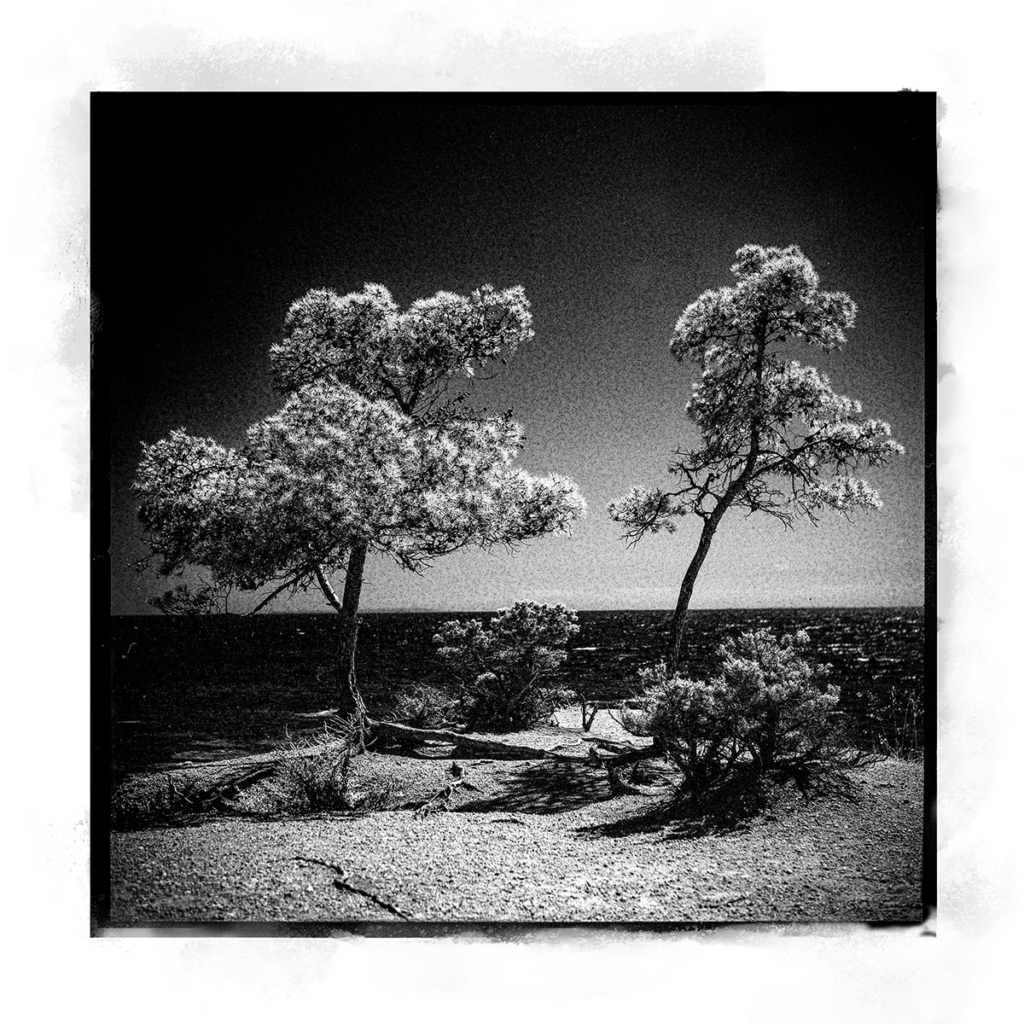

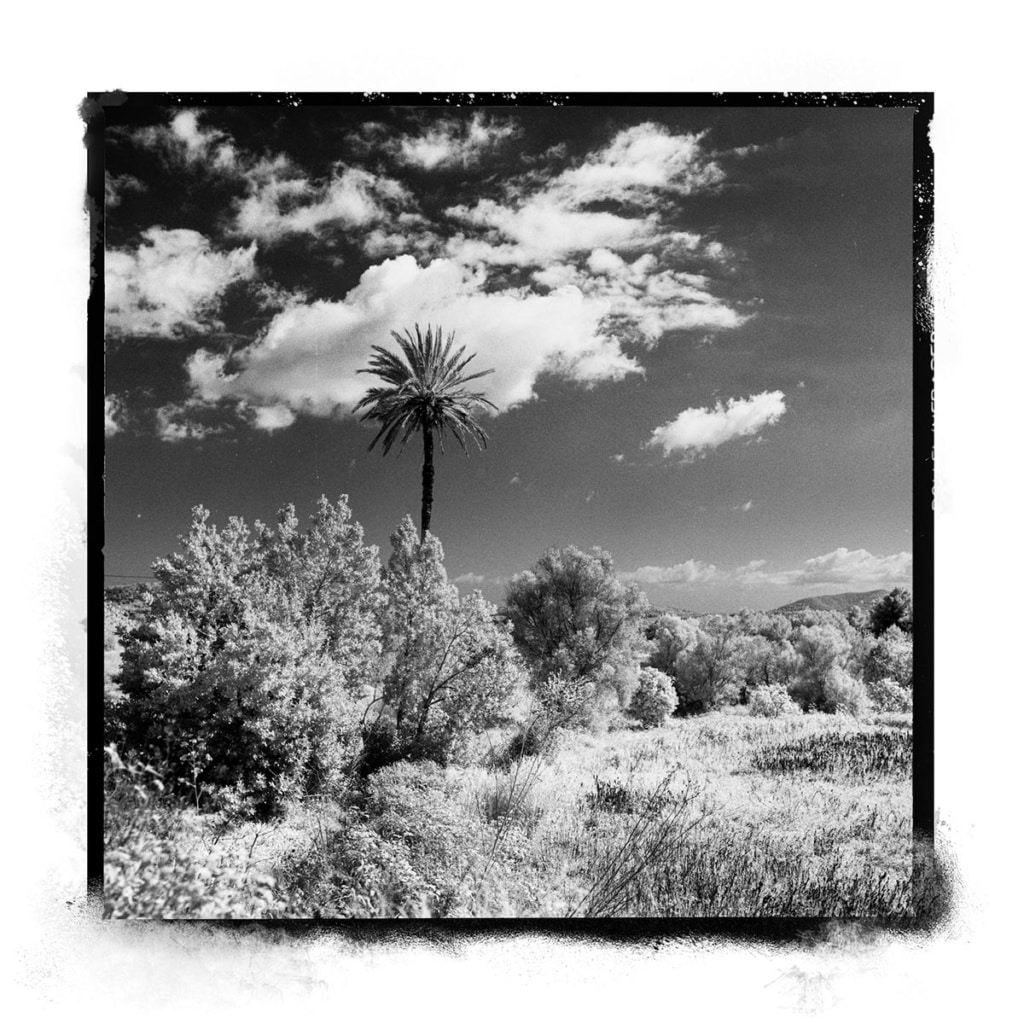

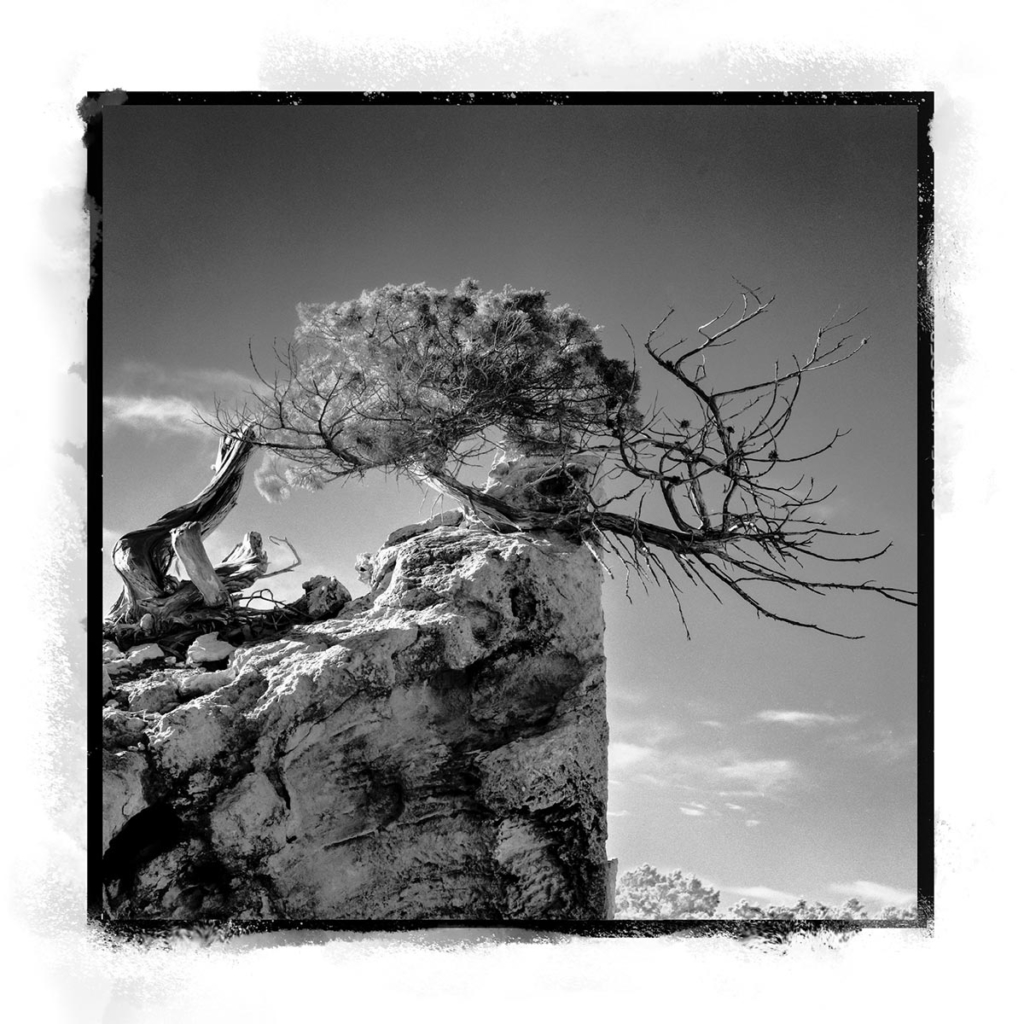

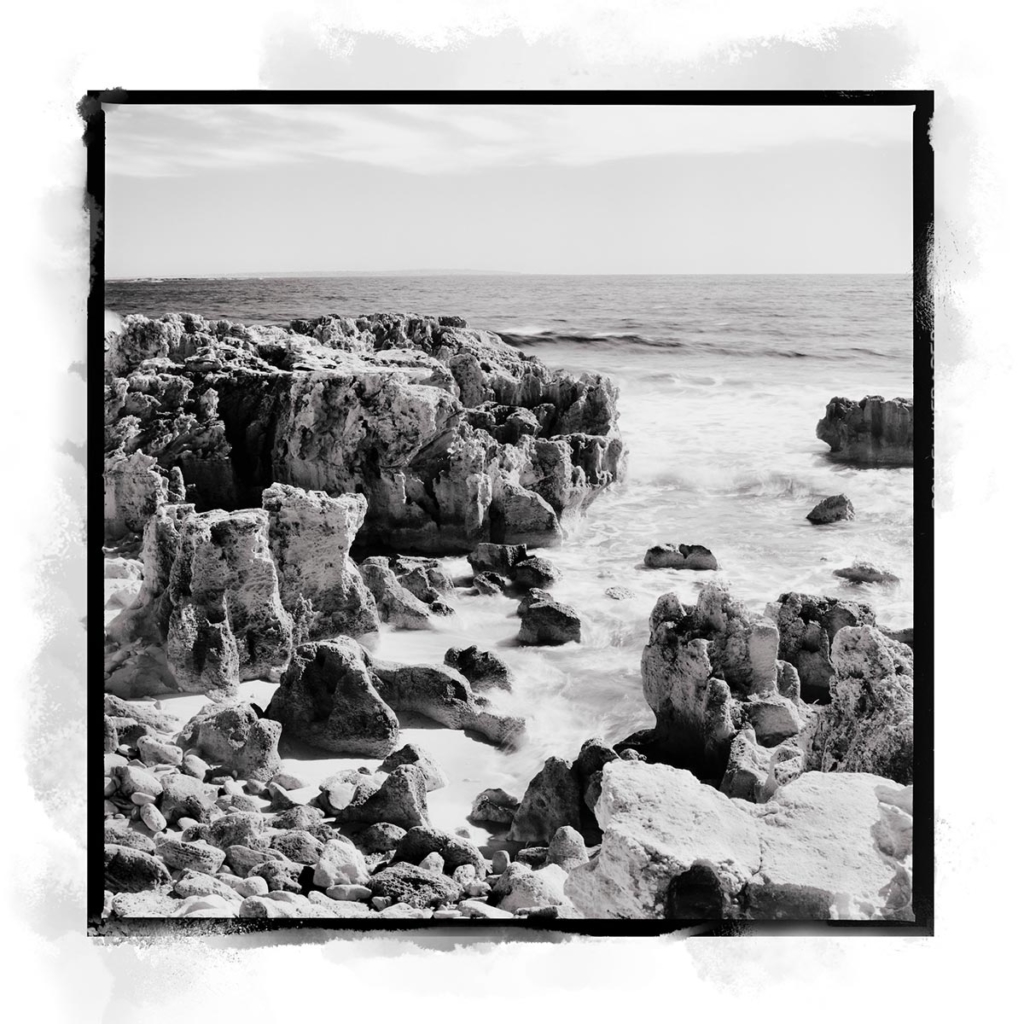

The magical light of Ibiza is predestined for this kind of photography.

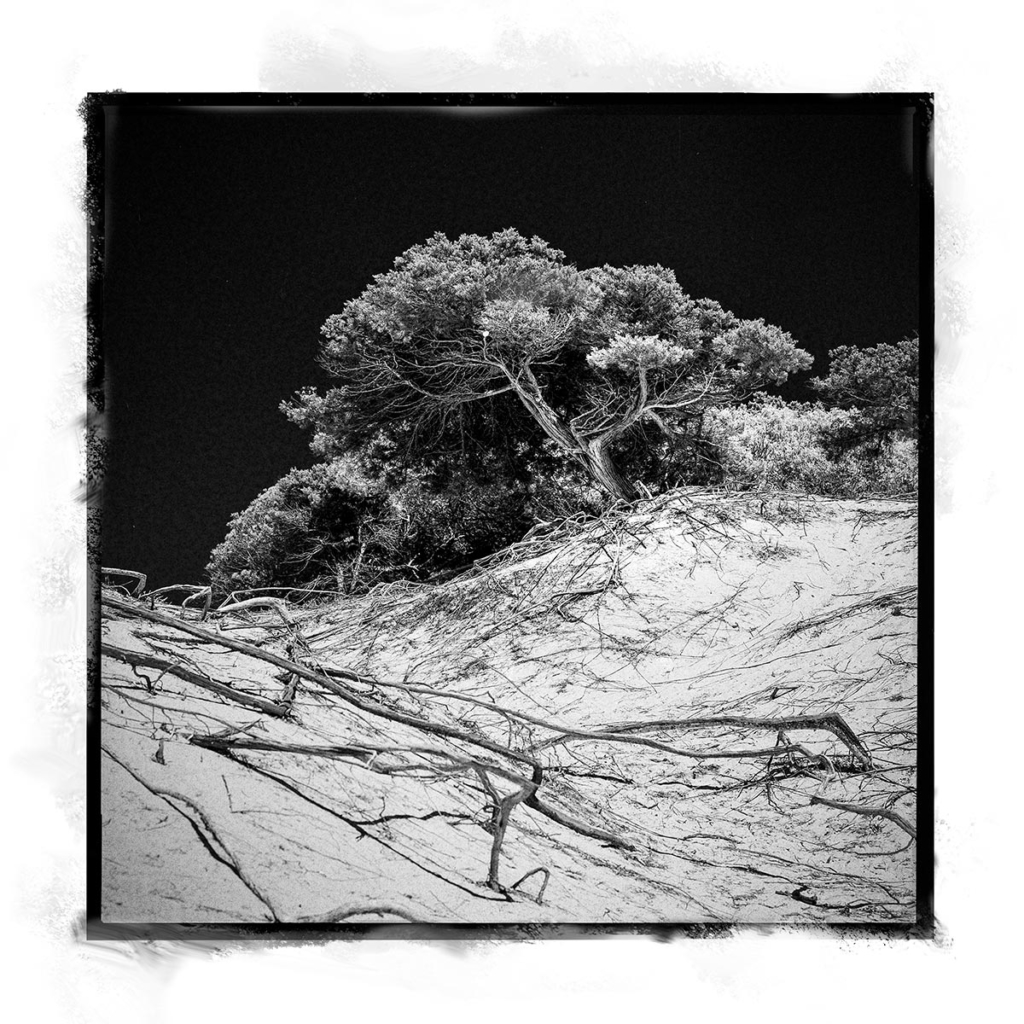

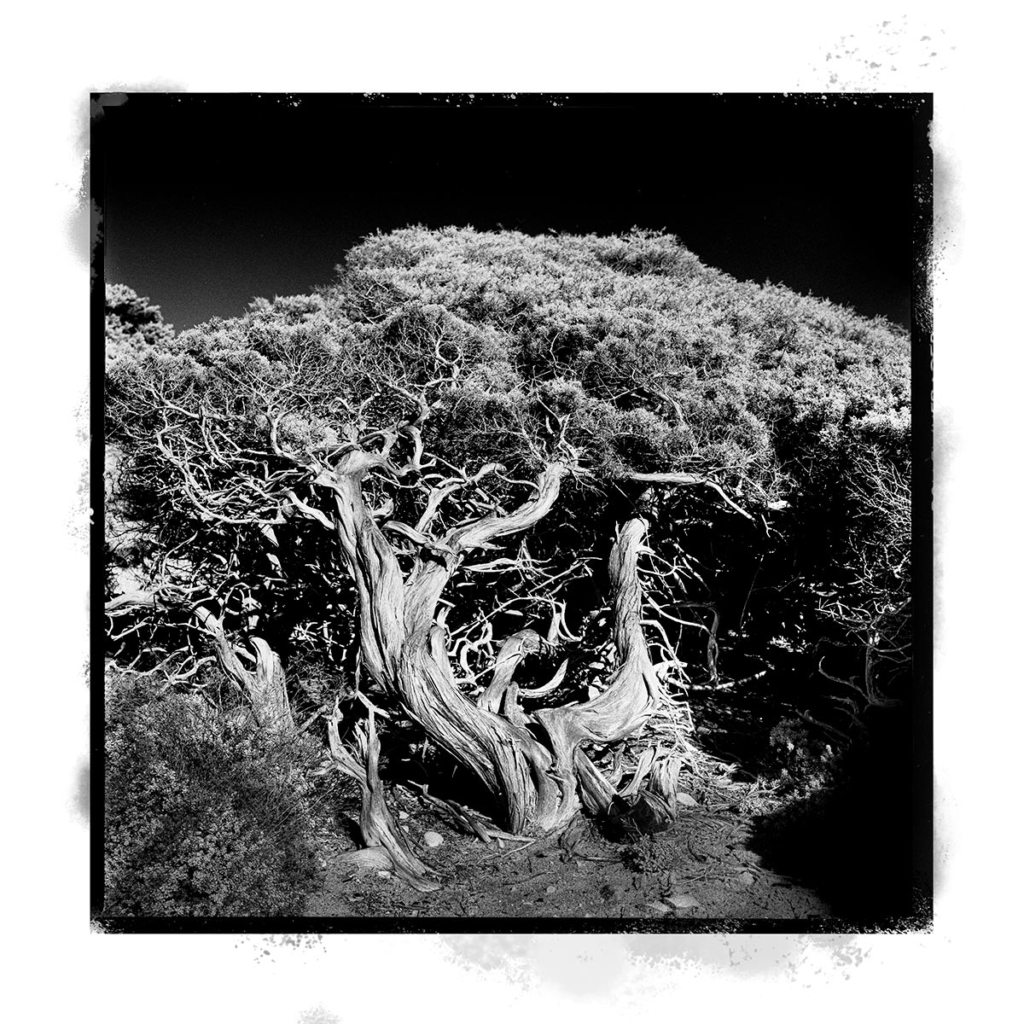

The unique light-flooded landscape of Ibiza is reproduced in the heat radiation that is invisible to us, but can be felt. The more heat the objects emit, the brighter they appear. Living green is bright, dead green is dark. Blue sky is black, clouds very white.

The camera lens must be blocked off with an opaque black filter (IR-720nm) to exclude visible light. This results in long exposure times and a tripod is mandatory.

This slowness forces a thorough creative examination of the motif and also does not allow an unlimited number of image variations. The shot has to be just right.

Unique pieces of a long, decelerated process.

At the end of the day, there is still nothing to see, because you have a black-and-white negative that still has to be developed and enlarged. These films, originally produced for the military, have extreme image sharpness. They use the potential of the lens to the limit. Unfortunately, films of this quality were not commercially available in the past. Therefore, it is surprising that in terms of sharpness of detail, these photos can rival modern digital files of 50 MP. But also the special look of the “real” analog photo is incomparable.

In the next step, the real bromide silver prints are not processed in the machine, but the developer solution is manually applied to the photo paper with a sponge. Hence the characteristic edges of the image. The paper blackens only where it has been wetted. Then fixing, watering, drying, just the usual procedure of analog photography.

Norbert Tölle sees himself only at the beginning of a long infrared photo series of photographic exploration of this beautiful island.